The #Asooke hashtag has been trending on Instagram for the past we decided to give a bit of a load down of its history and elegance. Aso Oke is not fabric—it’s art and symbol of pride of Yoruba Nigeria, Benin, and Togo culture. Aso Oke literally means “top cloth” in Yoruba and has been hand-stitched by talented craftsmen on hand-held narrow looms and woven into cultural expression, celebration, and status for centuries.

Historical Origin and Importance

Aso Oke started centuries ago in Yoruba kingdoms. It was first produced centuries ago primarily in the interior, particularly in such towns as Iseyin in Oyo State, where generations have passed on technique to one another. The people of early Lagos called the cloth “Aso awon ara ilu oke” (cloth of those from the interior), emphasizing its place of origin and prestige status. Over time, Aso Oke developed connotations of prestige and reserved for important ceremony occasions like weddings, naming ceremonies, and chiefs’ titles of chieftaincy.

The Weaving Process

Aso Oke is a heavy-textured fabric that demands unyielding dedication to heritage. We begin with strict screening of raw materials—primarily cotton and locally made or imported silk. The cotton is spun by the craftsmen themselves using natural dye like indigo to impart the deep, dark color characteristic of the fabric. The yarn so made is carefully wound onto a horizontal loom. The craft demands not only manual skill but also an expertise in creating designs because warp and weft are woven at right angles to achieve attractive and symbolic patterns. There actually are a fairly considerable number of steps to this old art form.

The yarns are prepared and then dyed first, and usually undergo multiple iterations of dyeing throughout the process of achieving rich depth of color. Then the loom is set up with the colored threads extended in the warp and the weft threaded through in a manner of careful care by traditional techniques—typically as “carryover” (njawu) or “openwork” (eleya)—to fabricate the typical patterns on Aso Oke cloths. The process tends to be communal with knowledge and skills transmitted from generation to generation, further serving to strengthen community bonds and cultural continuity.

Types and Variations

Aso Oke comes in a variety of hues, each holding a symbol. Most widely valued varieties are:

- Etu: Etu is usually deep indigo or near black with minimal, pale blue stripes. Dark color signifies dignity and is often utilized for ceremonial attire for men, such as the agbada (an unfitted robe).

- Sanyan: Sanyan is derived from a blend that contains the silk of the Anaphe moth and is recognized by its pale brown, sometimes beige, color. Its light color is widely used in men’s and women’s apparel.

- Alaari: Renowned for its deep red or magenta color, Alaari is linked with passion, energy, and celebration and hence is extremely popular during celebrations.

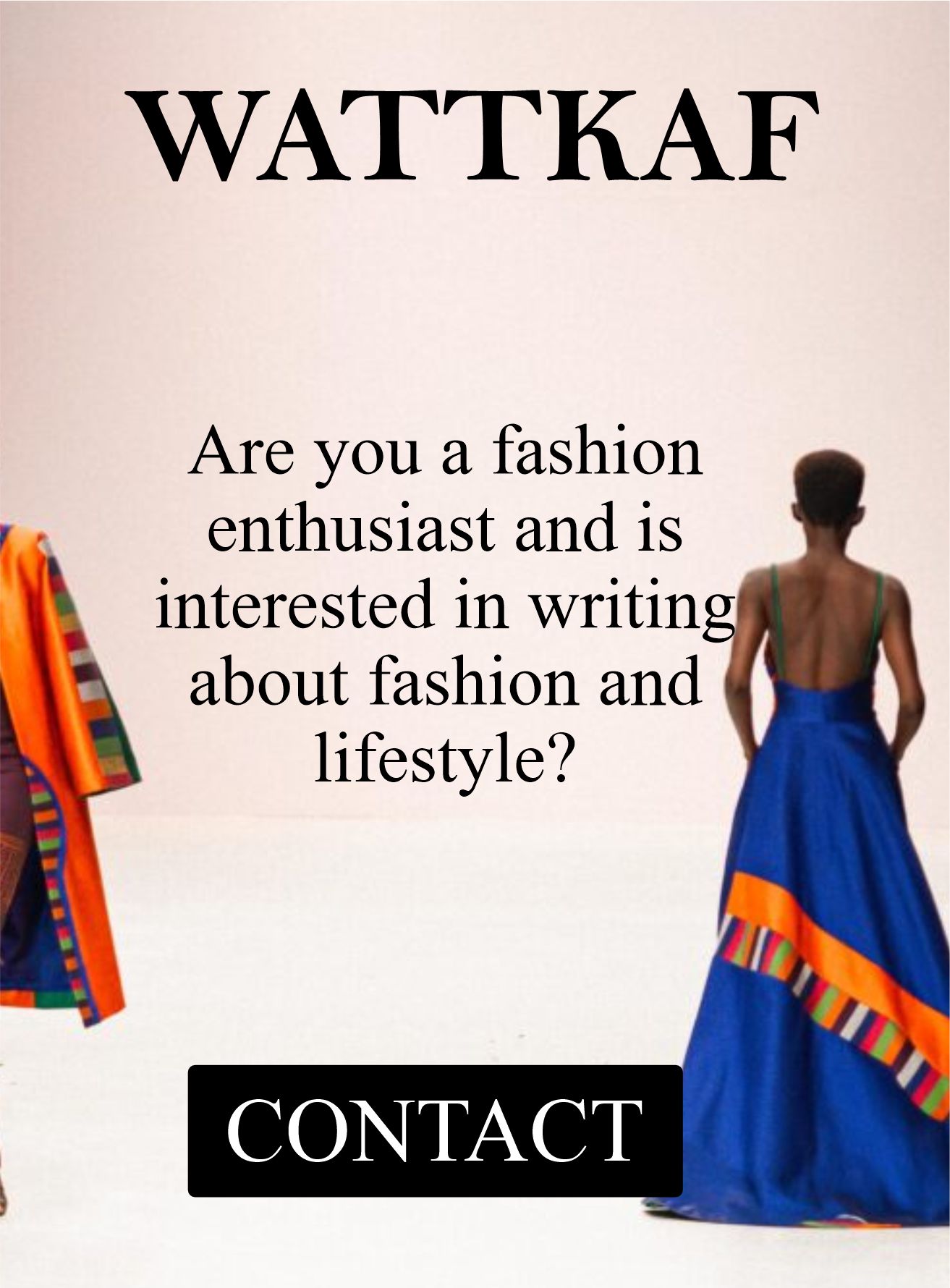

These other types sometimes are the products of new experimentation. Contemporary designers have the flexibility to merge traditional Aso Oke with other indigenous fabrics like Adire or even contemporary man-made materials in order to produce lighter and more adaptable materials that are suitable for daily purposes without giving up the cultural status of the original designs.

Cultural Role and Identity

Aso Oke in Yoruba culture is to be more than a piece of clothing; it is to be a permanent emblem of community pride and identity.

For the Yoruba, the cloth does speak—each pattern and color telling volumes about family heritage, social status, and religious faith. The availability of Aso Oke to be utilized in group attire (also known as “Aso Ebi”) also speaks to the communal bond forged by family reunions or unique events on the social calendar. The fabric is also at the heart of masquerades in the past, such as the Egungun festivals, where the garment is claimed to invoke ancestral spirits and demonstrate respect for heritage. Modern Yoruba still cherish Aso Oke as a representation of their heritage.

Although the old method of weaving continues, modern fashion designers have incorporated Aso Oke to create new-age apparel that honors traditional style but is appealing to international markets. Designers such as Tsemaye Binitie and the designers of Maki Oh have reimagined Aso Oke, meshing old-school craftsmanship with modern tailoring techniques. This fusion not only guarantees the survival of artisans but also tells a tale of empowerment amidst mass production.

Modern Interpretations and Global Popularity

Despite the challenges posed by foreign cloth and mass production, Aso Oke is experiencing a revival. The global luxury market, with its growing focus on sustainability and craftsmanship, has been long appreciative of the intrinsic worth of Nigerian hand-woven cloth. Young Nigerian entrepreneurs and older designers are now collaborating with Aso Oke—producing lighter cloth, new shades, and fusion designs mixing the traditional fabric with modern silhouettes. As they strut the world’s catwalks and participate in celebrity gatherings, they symbolize greater than cultural heritage and creative expression.

The history of Aso Oke is proof of the resilience of Yoruba art. Through its complex motif, richness in color, and lengthy process, Aso Oke is a bridge to history. It has a rich cultural voice—a voice of tradition, people, and the transformative power of art. With each subsequent reinterpretation by present-day Nigerian designers, Aso Oke remains a living legacy of African culture waiting to be passed along to future generations and overseas markets.